Updated December 19, 2025

Originally published Aug 14, 2024

“Recyclable” is one of the most widely used (and most misunderstood) terms in sustainable packaging.

Many consumers put something in the recycling bin and never know what happens next. Headlines like “only 5% of plastic is recycled” only add to the confusion, making it easy to assume recycling doesn’t work at all. The truth is more nuanced: a significant amount of packaging is recycled in the U.S., but only when several critical conditions are met.

In this two-part Deep Dive, we unpack what “recyclable” actually means for packaging. In Part 1 (this article), we focus on the criteria that determine recyclability. In Part 2, we’ll take a closer look at how material recovery facilities (MRFs) work in practice.

Before we begin, one important clarification: this Deep Dive is about packaging. Other products, like electronics, clothing, or mattresses, follow entirely different recycling pathways. We’ll return to that distinction at the end.

So what does “recyclable” mean?

At a high level, “recyclable” refers to materials or products that are regularly collected, sorted, and reprocessed into new products, rather than sent to landfill.

In practice, recyclability is not a simple yes-or-no question. A package must successfully move through multiple steps of the recycling system, and failure at any one step can mean it won’t be recycled at all.

It’s also critical to understand that packaging does not all move through the same recycling pathway.

- Business-to-consumer (B2C) packaging, the packaging that ends up in homes, is typically recycled through curbside programs and processed at MRFs.

- Business-to-business (B2B) packaging such as stretch wrap, corrugated cardboard, or pallets used in warehouses and distribution centers often follows entirely different collection and sorting systems.

A package may be recyclable in one context but not the other. When consumers hear that something is “recyclable,” they usually assume it belongs in their curbside bin. That assumption is one of the biggest sources of confusion in recycling today.

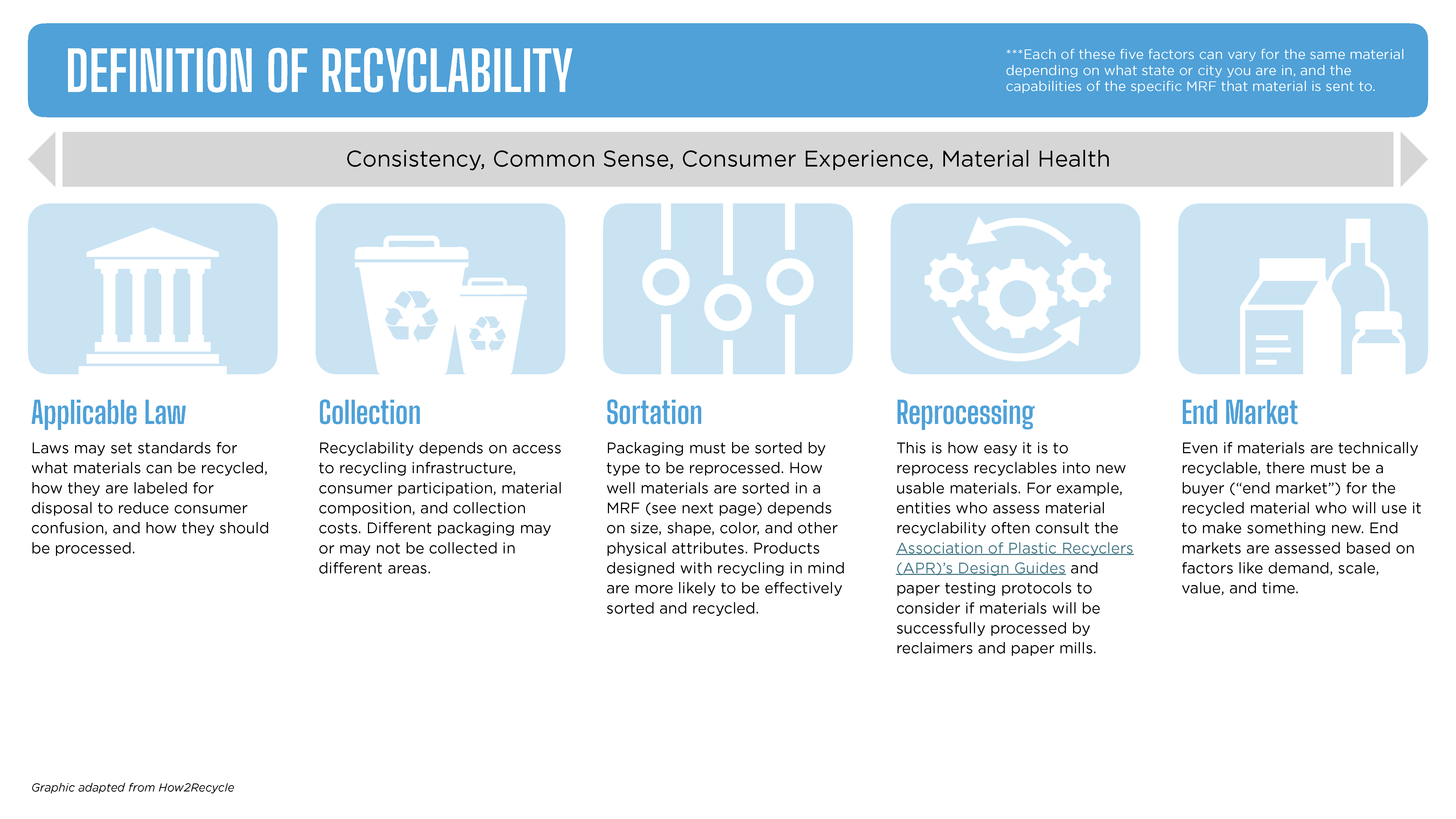

With that context in mind, let’s look at the five factors that generally define recyclability, as used by groups like How2Recycle, The Recycling Partnership, and the Sustainable Packaging Coalition.

Graphic adapted from How2Recycle

Applicable Law

When it comes to recyclability, the most direct role of law is defining what can and cannot be labeled “recyclable.”

In the U.S., environmental marketing claims are governed at the federal level by the Federal Trade Commission’s Green Guides, which set standards for when it is appropriate to label a product or package as recyclable. In short, a package should only be labeled “recyclable” if it is collected, sorted, and reprocessed by a meaningful portion of the population, and if recycling pathways actually exist in practice, not just in theory.

Increasingly, states are building on this foundation with their own labeling laws. California’s SB 343, often referred to as a “Truth in Labeling” law, is a prominent example. SB 343 restricts the use of the chasing arrows symbol and other recyclability claims on plastic packaging unless the package meets specific, data-driven criteria defined by the state, including minimum thresholds for collection, sorting, and end markets. The goal of these laws is to reduce consumer confusion and ensure that recyclability claims reflect real-world outcomes.

Because these labeling laws are evolving and sometimes differ by jurisdiction, they play a central role in how brands assess and communicate recyclability. Programs like How2Recycle continuously update their guidance to stay aligned with the FTC Green Guides and emerging state-level requirements in the U.S., as well as similar regulations in Canada.

Beyond labeling, laws can also influence whether materials are recycled in practice.

Some regulations require certain materials to be separated from the waste stream or restrict their disposal in landfills, which can improve material quality and recycling rates. Others create financial incentives that dramatically increase collection. Deposit return schemes (DRS), commonly known as bottle bills, are a well-established example. By attaching a refundable deposit to beverage containers, DRS programs significantly increase return rates and reduce litter. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) laws, now being implemented in several U.S. states, are another mechanism, shifting some of the financial responsibility for recycling systems onto producers and helping fund infrastructure improvements.

While these mandates and incentives do not, by themselves, make a package recyclable, they can meaningfully change the conditions under which recycling occurs. In other words, laws shape not just what can be called recyclable, but also how likely it is that recycling actually happens.

Collection

Collection is the first and most fundamental step in the recycling process. If a package isn’t collected, it isn’t really recyclable, no matter how well it’s designed.

Collection can take many forms:

- Curbside recycling

- Store drop-off programs

- Centralized drop sites

- Mail-back or take-back programs

For consumer-facing packaging, curbside recycling is generally the gold standard because it is the most familiar and convenient system for households. Access matters. Many rural communities and multi-family housing complexes still lack consistent recycling services or face limitations on what materials are accepted. Because of this, recyclability assessments often use a 60% access threshold: if at least 60% of the U.S. population has convenient access to a program that collects a material, it is generally considered “commonly collected.”

Economics matter too. Recycling is not just an environmental service; it’s a business. Collectors and MRFs operate by selling materials to reprocessors. If a material has little or no resale value, it is unlikely to be collected consistently, regardless of its technical recyclability.

This dynamic often looks very different for B2B packaging. In warehouses, retail backrooms, and distribution centers, materials like corrugated cardboard or stretch film are often collected separately, baled onsite, and sold directly to reprocessors. These source-separated systems typically produce cleaner, higher-value material, and are one reason some materials are widely recycled in B2B settings but not in curbside programs.

Sortability

In most U.S. households, recycling is single-stream: paper, plastics, metals, and glass all go into the same bin. Before those materials can be sold, they must be separated by type, usually at a MRF.

Sorting accuracy is critical. Cleaner, more consistent bales command higher prices. Contamination lowers value and can make material unsellable.

Design choices strongly influence sortability:

- Single-material packaging is easier to sort than multi-material structures

- Very small items can fall through sorting equipment

- Flat items may be misidentified (for example, plastic lids mistaken for paper)

- Labels, inks, adhesives, and shrink sleeves can interfere with optical sorting

Packages designed with recycling in mind, considering things like size, shape, material purity, and ease of identification, are far more likely to be sorted correctly. Again, B2B packaging often follows a different path. Because materials are frequently source-separated before collection, they may bypass MRFs entirely, resulting in higher-quality bales and fewer sorting challenges.The physical mechanics of sorting are complex, and we’ll explore them in detail in Part 2 of this Deep Dive.

Reprocessability

Once materials have been collected, sorted, and baled, whether at a MRF for residential recyclables or through source-separated commercial systems, they are sold to reprocessors, who use them as feedstock to make new products. Just as manufacturers require consistent, high-quality raw materials, reprocessors depend on clean, predictable inputs. Packaging that is designed to be easy to reprocess, typically by using a single material, minimizing additives, and avoiding contaminants, is far more likely to be recycled in practice.

One of the biggest barriers to reprocessing is material complexity. Packaging made from multiple substrates (for example, plastic-paper laminates or plastic-metal hybrids) can be extremely difficult or impossible to separate at scale. Even when each individual material is theoretically recyclable on its own, combining them can prevent successful reprocessing altogether. Contamination from food residue, adhesives, inks, or incompatible layers can further reduce the quality of the recycled output or require additional cleaning steps that increase cost.

Plastics introduce another layer of complexity. While consumers often think of plastic as a single category, packaging professionals know that there are many different resin types with distinct chemistries and melting points. Most mechanical recycling systems require these resins to be separated to produce usable recycled material. Contamination from incompatible plastics is a persistent challenge for reprocessors and can significantly lower the quality or usability of recycled resin. For this reason, recyclability assessments and packaging design decisions often reference the Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR)’s Design Guides, which outline known reprocessing challenges and preferred design attributes.

Paper-based packaging has its own considerations. When paper is coated, laminated, or combined with plastic or other materials, it may be difficult to repulp and recover usable fiber, even if the base paper itself is recyclable. In these cases, repulpability and recyclability testing can help assess how much fiber can actually be recovered. Established test methods, as the Fibre Box Association’s Voluntary Protocol often performed at Western Michigan University (WMU), exist for this purpose, and many brands rely on them when evaluating complex paper-based packaging.

Packaging that is able to be reprocessed into a new material is often referred to as “technically recyclable.” It’s not uncommon to hear that a package is technically recyclable but not recycled in practice because of some other challenge having to do with collection, sortation, etc. The availability and maturity of reprocessing technology also plays a major role. Materials that can be processed efficiently using existing, widely deployed infrastructure, such as repulping for paper or grinding, washing, and remelting for plastics, are more likely to be recycled at scale. Some products are incompatible with standard reprocessing methods or require specialized equipment that is not broadly available.

Emerging technologies, including those often grouped under the umbrella of “chemical recycling,” may eventually expand reprocessing options for certain hard-to-recycle materials. However, from a recyclability standpoint, what matters most today is whether a material can be reprocessed reliably, economically, and at scale using current systems. Claims of recyclability generally reflect present-day realities, not future potential.

In short, reprocessability sits at the intersection of material design, contamination control, and technological feasibility. Even well-collected and well-sorted materials can fail at this stage if they cannot be turned into high-quality, usable feedstock for new products.

End Markets

Even if a material can technically be recycled, it won’t be recycled without a buyer.

MRFs and collectors rely on stable end markets — manufacturers willing to purchase recycled material at viable prices. If demand is weak, inconsistent, or highly regional, materials may be excluded from recycling programs. End markets also impose quality standards. Lower-grade bales fetch lower prices and may be downcycled into lower-value products — or rejected entirely. Strong, stable end markets are essential to keeping recycling systems functional. Advances in recycling and manufacturing technology can strengthen end markets over time, but they must be economically viable and scalable to make a meaningful difference.

——-

To be truly recyclable, a package must succeed at every step of this system — and those conditions vary by location, infrastructure, and market dynamics. This creates real challenges for brands and packaging designers. Improving one factor (like material purity) does not guarantee recyclability if collection access, sortation capability, or end markets fall short. Recyclability is a systems challenge, not just a design challenge.

In Part 2, we’ll take a closer look at MRFs — where many of these factors converge.

A quick note on non-packaging products

You may see products like clothing, electronics, or mattresses labeled as recyclable. These claims can be legitimate, but they do not mean those items belong in your curbside bin.

Unlike packaging, these products are typically recycled through specialized collection systems, such as take-back programs or dedicated processing facilities. When labels don’t clearly explain this distinction, consumer confusion is inevitable.

Improving recycling outcomes will require not just better packaging design, but clearer communication about how and where different products should be recycled.

Where to go from here?

- Visit our library of all our Deep Dives articles here

- Check out our Sustainability Terms Glossary, where we’ll add key terms from each of our Deep Dives over time.

- Sign up for our Deep Dive LinkedIn Newsletter and get these articles delivered straight to your inbox every month.

- Bookmark these pages for future reference!