Also, check out our Sustainability Terms Glossary, where we’ll add key terms from each of our Deep Dives over time. Bookmark this page for future reference!

From packaging food to online shopping, we commonly encounter flexible plastic packaging and films in our lives. Despite its abundance, flexible plastic packaging is not easily recycled. In our previous two-part Deep Dive on recycling, we covered different recycling programs and streams, and we described the problems flexible plastics and films cause for Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) (Part 1, Part 2). We also briefly touched on the store drop-off (SDO) system for recycling flexible films, but you still may be wondering, “what really is the SDO system, and how effective is it?”

In this Deep Dive, we will describe the SDO system and dive into its effectiveness, where the material ends up, how this recycling system was created, and how it can be improved.

What is the Store Drop-Off (SDO) System for Flexible Plastics?

When we refer to the store drop-off system here, we are referring to the U.S.-based recycling method where specific types of recyclable plastic materials, typically plastic films and flexible packaging, are collected at designated retail or grocery store locations for recycling. Unlike curbside recycling where consumers place their commonly collected recyclables into their household bins, this system provides a solution for items that are not accepted by most municipal recycling programs due to their lightweight, flexible nature. As we covered in our previous Deep Dive, these films present problems in MRFs so are generally not accepted there and need to be recovered through other means. The idea behind SDO is to collect specific plastic materials that cannot be processed effectively in curbside recycling programs and provide an alternative collection system to reduce landfill waste and plastic pollution.

When we refer to the store drop-off system here, we are referring to the U.S.-based recycling method where specific types of recyclable plastic materials, typically plastic films and flexible packaging, are collected at designated retail or grocery store locations for recycling. Unlike curbside recycling where consumers place their commonly collected recyclables into their household bins, this system provides a solution for items that are not accepted by most municipal recycling programs due to their lightweight, flexible nature. As we covered in our previous Deep Dive, these films present problems in MRFs so are generally not accepted there and need to be recovered through other means. The idea behind SDO is to collect specific plastic materials that cannot be processed effectively in curbside recycling programs and provide an alternative collection system to reduce landfill waste and plastic pollution.

In the U.S. SDO system, consumers bring clean, dry plastic film items — such as grocery bags, bubble wrap, and shrink bundling film — to designated drop-off points. These drop-off points are typically found at retail and grocery stores that choose to participate in plastic film recycling programs. Participating stores have collection bins for these specific materials, usually near the entrance of the store. The store periodically collects the materials from the bins and sends them to qualified recycling facilities to be processed into new products. We will dive deeper into the types of products these materials can be recycled into later.

This system for recycling flexible packaging was based on earlier plastic bag recycling programs. Many large retailers, such as grocery chains and department stores, started offering plastic bag recycling programs in the 1990s and 2000s. Like the current SDO system, customers were encouraged to return used plastic bags to collection bins at the store, which would later be sent to specialized recyclers. Over time, the program expanded to include other types of flexible plastic films (e.g., shrink wrap, bread bags, etc.). The SDO system was also based on the understanding that certain flexible packaging materials, like low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE), can be recycled if collected properly (“source-separated”). Partnerships between retailers and specialized recyclers enabled these materials to be diverted from landfills and turned into new products. The initial plastic bag recycling program provided the infrastructure and consumer habits needed for store drop-off systems. It also demonstrated that a take-back model could work outside traditional curbside recycling.

This system for recycling flexible packaging was based on earlier plastic bag recycling programs. Many large retailers, such as grocery chains and department stores, started offering plastic bag recycling programs in the 1990s and 2000s. Like the current SDO system, customers were encouraged to return used plastic bags to collection bins at the store, which would later be sent to specialized recyclers. Over time, the program expanded to include other types of flexible plastic films (e.g., shrink wrap, bread bags, etc.). The SDO system was also based on the understanding that certain flexible packaging materials, like low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE), can be recycled if collected properly (“source-separated”). Partnerships between retailers and specialized recyclers enabled these materials to be diverted from landfills and turned into new products. The initial plastic bag recycling program provided the infrastructure and consumer habits needed for store drop-off systems. It also demonstrated that a take-back model could work outside traditional curbside recycling.

Most drop-off points accept and collect films and flexible packaging made from polyethylene (PE) labeled as #2 or #4 plastics. Flexible plastic packaging and films are often made of materials such as PE, which can be recycled if collected and processed correctly. Specific plastic products accepted by the SDO system include:

- Plastic shopping, bread, and produce bags

- Newspaper sleeves

- Flexible plastic overwrap (e.g., around toilet paper or paper towels)

- Shrink wrap (e.g., around a case of water bottles)

- Shipping and packaging materials (e.g., compatible mailers, deflated air cushions, and bubble wrap)

- Plastic product wrappers (from toilet paper, diapers, etc.)

- Dry cleaning bags

- Ziplock and other re-sealable bags (clean and dry)

Like curbside recycling systems, the store drop-off system deals with contamination that can negatively impact the recycling process and end products. One of the largest sources of contamination for SDO includes films with food residue on them and films that are multilayer or have metalized layers. Before they are dropped off, items should be cleaned and dried to prevent contamination; in some cases, you may need to remove labels or tape from the packaging. These contaminates can make the material harder to recycle (by burning in the recycling process, causing black spots or darkening of resin), and this ultimately reduces the PCR resin quality.

Like curbside recycling systems, the store drop-off system deals with contamination that can negatively impact the recycling process and end products. One of the largest sources of contamination for SDO includes films with food residue on them and films that are multilayer or have metalized layers. Before they are dropped off, items should be cleaned and dried to prevent contamination; in some cases, you may need to remove labels or tape from the packaging. These contaminates can make the material harder to recycle (by burning in the recycling process, causing black spots or darkening of resin), and this ultimately reduces the PCR resin quality.

Some products to avoid recycling through SDO altogether include food wrap or cling wrap, rigid plastics, prepackaged food bags, biodegradable or compostable plastics, chip bags or candy wrappers with mixed materials, and plastic film that has excessive glue residue.

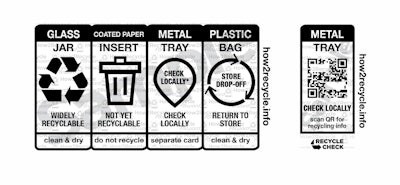

In an effort to help consumers decide how to properly dispose of these flexible materials and reduce confusion, How2Recycle released a “Store Drop-Off Label” to put on compatible flexible plastic packaging. Here is an example of what an SDO label on a package may look like, although as of this writing, How2Recycle is currently in the process of revamping the labels (drafts below).

The End Markets for SDO Materials

Materials collected through store drop-off recycling programs go through a specialized recycling process that is distinct from curbside recycling. These materials are consolidated and transported from drop-off points to recycling centers or plastic film recycling facilities that are equipped to handle flexible plastics. Retailers usually work with these recycling partners to manage transferring the materials. At these recycling facilities, the plastic is usually melted down and the resin is used to create various new products.

Before we dive into some of the common end products for these materials, it’s important to describe how their value may differ in terms of upcycling or downcycling the material. Upcycling involves converting materials into products of higher value or quality, often adding new functionality or improving their aesthetics. Upcycled products are typically more durable, valuable, or innovative than their original form, extending their use in a meaningful way.

Before we dive into some of the common end products for these materials, it’s important to describe how their value may differ in terms of upcycling or downcycling the material. Upcycling involves converting materials into products of higher value or quality, often adding new functionality or improving their aesthetics. Upcycled products are typically more durable, valuable, or innovative than their original form, extending their use in a meaningful way.

Upcycling can be as simple as using a glass jar as a storage container or flower vase, or as complex as taking wooden pallets and turning them into functional furniture like coffee tables. In the context of SDO materials, possible avenues to upcycle these recyclables include products like filament for 3D printing, handicrafts like jewelry and bags, high-end product packaging, art installations, outdoor gear (weather-resistant backpacks and tents), and more. However, the end markets for these applications are niche and not very scalable or widely available currently.

Downcycling, on the other hand, converts materials into items of lower value or quality, and the end products may not be recyclable again after their new use. The most common end market for SDO materials is currently to send recycled material to a company like Trex, which uses the material to create lumber for decking, roofing, and other related applications. Other examples of downcycling SDO materials include turning the material into durable goods (outdoor furniture, trash cans, car parts like mud flaps, etc.), liner bags for trashcans, and plastic shipping pallets, to name a few.

Downcycling, on the other hand, converts materials into items of lower value or quality, and the end products may not be recyclable again after their new use. The most common end market for SDO materials is currently to send recycled material to a company like Trex, which uses the material to create lumber for decking, roofing, and other related applications. Other examples of downcycling SDO materials include turning the material into durable goods (outdoor furniture, trash cans, car parts like mud flaps, etc.), liner bags for trashcans, and plastic shipping pallets, to name a few.

Ultimately, upcycling aims to enhance the material’s worth, while downcycling tends to reduce it and lead to products with limited future recyclability. Upcycling contributes to a more circular economy, ensuring materials maintain their highest and best use, whereas downcycling can be seen as simply temporarily delaying their path to landfills. Even though the secondary product is often not recycled, downcycling still provides important avenues to divert these materials from landfills and provide a second use for them. Flexible plastic packaging and films are most often “downcycled” into products of lower quality because the current recycling infrastructure, economics (cost to produce products and available end markets), and the materials themselves don’t lend well to upcycling into higher-value or more reusable materials. Contamination from food residue or non-recyclable materials (e.g., labels, adhesives, inks, and metalized coatings) makes it more difficult to process materials into high-quality recycled products and pushes them toward downcycling, reducing their chances of being recycled again after their second lives.

While upcycling flexible plastics from store drop-off systems is less common than downcycling, there are several methods in development that may be promising paths to recycling and offer exciting potential for transforming flexible plastics into higher-value, more functional products. It will be important to continue building and supporting end markets that upcycle these materials and keep them in use. Specifically, recycled content should be incorporated into more consumer flexible film products where possible to prop up these end markets.

Is SDO Effective & Sustainable?

In theory, the SDO system for flexible packaging sounds like a great outlet for a material that rarely makes it through a MRF. However, recent investigations have revealed a severe lack of transparency about what happens to the collected material from SDO bins. The system is effective in the sense that it provides a source-separated stream that is cleaner than your typical curbside bin; however, it is not effective in the sense that many people don’t know about it or where to find SDO locations, and whether their materials make it to recycling facilities is unclear.

The biggest gap for consumers with SDO is they don’t know that it exists, and/or they don’t know how to find active drop-off locations. To try and close this gap, the first nationwide film recycling directory was launched in 2007, which showed consumers where they could find local drop-off points and the accepted materials for each location. The directory was maintained by Stina Inc., a longtime recycling consulting firm, since its creation and up until its removal in November 2023. The directory also intended to verify that the collected plastics were sent to processors and end markets outside of landfill and incineration. However, this verification was a labor-intensive process that Stina could not maintain. The removal of the directory followed several high-profile indictments of drop-off film recycling, specifically questioning whether SDO materials made it to an end market. These investigations revealed an alarming amount of SDO plastics ended up at landfills or trash incinerators, and some of the listed collection points were not accurate. On top of unreliable disposal, there were various locations listed on the directory that did not actually have SDO bins in their store for consumers to drop materials in. As a result of these findings, and to avoid amplifying inaccurate information around the SDO system, Stina decided to take down its directory altogether.

It’s important to make a distinction between the two main sources of flexible materials at most retail stores, the “front-of-house” (FOH) versus the “back-of-house” (BOH). BOH refers to all the areas where customers are not expected (delivery rooms, stockrooms, etc.), while FOH represents the public-facing area of a business where, if the store participates, SDO collection bins are located. Adding to consumer skepticism about the true recycling rates of their returned materials, the majority of plastic film material sent to specialized facilities to be recycled is usually generated from the BOH of participating stores not FOH, where consumers bring their materials via SDO. The recycling of plastic films benefits immensely from the amount of material generated at BOH from things like stretch film cut from pallets that is much cleaner than materials with more inks and residue on them collected FOH via SDO. This means the material collected from BOH is more likely to make it to a recycling facility than thrown away or incinerated compared to the consumer materials generated at FOH. Furthermore, there is simply much more volume with BOH items than FOH.

As a result of all these findings, some view SDO as a hollow greenwashing tactic used to satisfy corporate commitments and goals set around adopting recyclable, compostable, or reusable packaging in operations, without companies actually addressing the root causes of their plastic waste and the general overuse of plastic. Essentially, they make it look like they are tackling the plastic waste generated by their products by labeling them as recyclable via SDO. However, some critics say that customers are misled about the recyclability of these products and packaging because consumers tend not to understand the difference between SDO- and curbside-recyclable. Additionally, plastic films continue to be recycled at very low rates. Commercial films generated at BOH have an estimated recycling rate of 21%, while residential films and flexible packaging have a recycling rate of only 2-4% according to findings from Closed Loop Partners and the Flexible Packaging Association.

These suspicions around true sustainability benefits and greenwashing raise the question – is this system sustainable? As we mentioned, the main end market for SDO material has been, and continues to be, Trex decking. While this is by no means a horrible outcome, it still represents downcycling. To build a better sustainability case, it would be better if the material could return to its original use as flexible packaging. In other words, the end markets for this recycled material should be shifting toward incorporating PCR content from SDO materials into flexible packaging on a large scale. As recycling technologies and innovations improve, more opportunities for upcycling flexible films and plastics are expected to develop, helping reduce the environmental impact of these materials and creating more sustainable end markets.

How Recycling for Film and Flexibles Can be Improved

Like traditional curbside recycling, one of the biggest issues with recycling consumer flexible packaging is contamination. To minimize contamination levels, it is critical that consumers are well-informed about which items are accepted in store drop-off recycling programs, in addition to other limitations. For example, films that have food residue on them pose challenges, as do plastic films that are not PE, such as polypropylene (PP, #5 plastic) films. Brands must provide clear labeling on packaging to help combat that contamination, and substantially more effective consumer education about the existence of SDO must be done.

In addition to the hurdles around raising consumer trust and participation in SDO, the system faces challenges with participating retailers. Participating in SDO is something retailers do voluntarily, and managing this system is not easy, nor is it their first job. To be successful, organizations working to improve SDO’s effectiveness and transparency need to work around the retailer’s internal systems. They must accommodate the retailers’ busy times and seasons in a way that doesn’t disrupt operations or draw away resources, which is not an easy task! However, taking the time to make SDO easier and more manageable for retailers to participate in will ultimately help to increase available drop-off points for consumers and accurate data reporting.

All this information may have left you wondering, “so is the SDO system even worth it?” And, our answer is, yes, we think it is, although preferably as a short-term solution. Despite faith lost in the current SDO system, extensive work is being done to build a better system in which consumer materials are being recycled into new products, with greater levels of transparency, trust, and reliable data. Ultimately, the goal is to get to a system where films and flexible packaging can be recycled curbside, shifting the responsibility of managing these materials from retailers to municipalities, hopefully making it easier for consumers to participate. However, to get to widespread film recycling, we need to start with SDO because it is the only consumer-facing avenue we have to recycle film today. It will be necessary to first invest in SDO and build consumer trust in the system to demonstrate for households that there is a way to recycle their films if they can be collected. As new methods of collecting film and flexible packaging may develop, and as residential recycling pilots may graduate into widespread systems, it is important to keep supporting the store drop-off stream to try and divert these materials from landfills in the meantime.

To address the current need for an accurate nationwide directory, The Flexible Film Recycling Alliance (FFRA), created by The Plastics Industry Association, will be releasing a new SDO directory to empower consumers to accurately find their nearest participating retailers. With this new directory, launching this fall, consumers can confidently locate local retailers who participate in SDO and the specific materials each location accepts. The directory is accompanied by traceable data and validated store information. It will also be validated by GreenBlue with a methodology developed by Resource Recycling Systems (RRS), so consumers can be confident the locations offered by the directory are active and accurate and their materials are making it to reprocessors.

In the U.S., only 1% of consumers can recycle films and flexibles through curbside recycling right now, but a variety of stakeholders are working on changing this, notably The Recycling Partnership’s Film and Flexibles Coalition. The SDO system has been developed around retail infrastructure to manage their materials, but it can be used to step into a more municipal management of these materials with a curbside system. By establishing greater trust with both consumers and retailers, stakeholders like FFRA, The Recycling Partnership, and SPC can help to work toward a more efficient, transparent, and impactful system for collecting consumer flexible films and packaging.

Read Part 2 to learn more about when companies should consider using store drop-off-eligible films!

Additional Resources:

More info on the How2Recycle store drop-off label for flexible packaging: https://how2recycle.info/about-the-how2recycle-label/store-drop-off-us-only

Dive deeper into the new national Film Recycling Directory by FFRA: https://www.packagingdive.com/news/plastic-flexible-film-recycling-alliance-launches/710498

Read about ABC’s store drop-off investigation: https://abcnews.go.com/US/put-dozens-trackers-plastic-bags-recycling-trashed/story?id=99509422

Learn more about How2Recycle’s in-depth study on store drop-off recyclability and the future of SDO packaging design: https://greenblue.org/2024/01/05/report-the-future-of-store-drop-off-recyclability